Recent archaeological explorations in the Carpathian Basin of Hungary have yielded a groundbreaking discovery that challenges our understanding of gender roles during the 10th century. For the first time, a female burial containing weaponry has been documented at the Sárrétudvari-Hízóföld cemetery, revealing layers of complexity regarding the societal positions of women in a tumultuous era characterized by conquest and conflict.

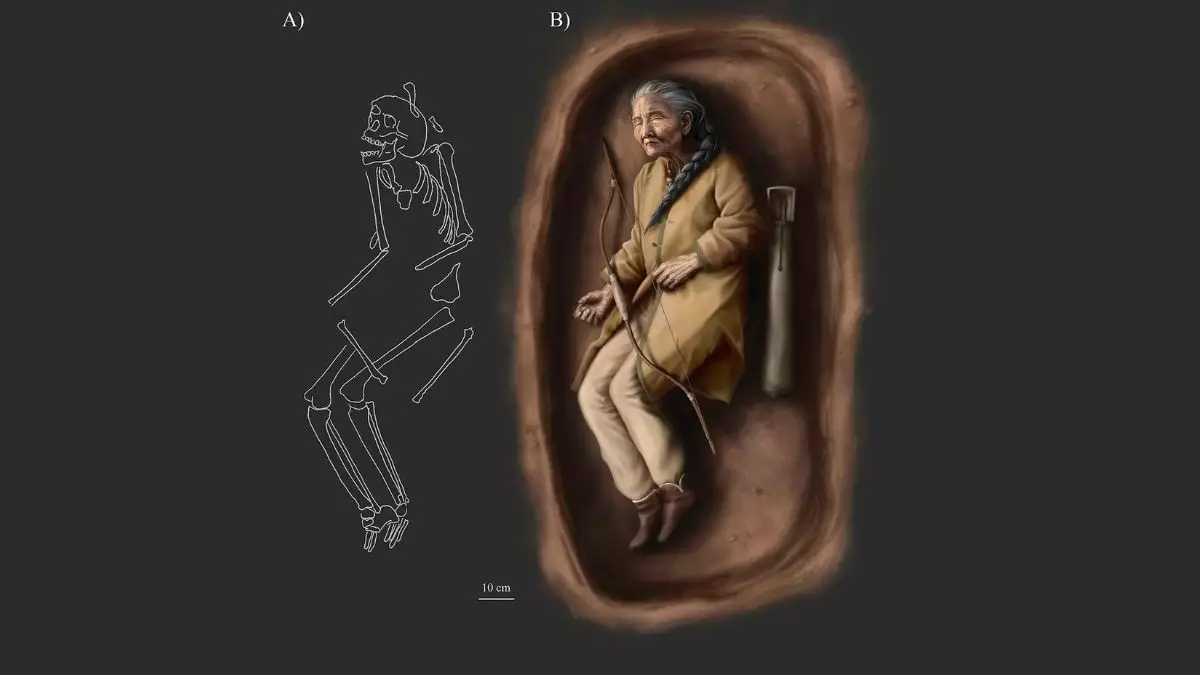

The implications of this discovery stretch far beyond the mere facts of the burial. Led by renowned researcher Dr. Balázs Tihanyi, the study unearthed a wealth of grave goods alongside skeletal remains, including a silver penannular hair ring, bell buttons, and items associated with archery. The presence of conventional weaponry, such as arrowheads and quiver components, indicates a multifaceted identity for the individual identified as SH-63. This burial stands out in what is typically recognized as a male-dominated cemetery context, suggesting a nuanced blend of gender roles and a potential reevaluation of societal norms of the time.

Traditionally, archaeological evidence has painted women of this era as fundamentally separated from martial pursuits. The identification of SH-63 as a female, despite the challenging preservation status of her remains, ignites a critical interdisciplinary dialogue among historians and archaeologists alike. However, Dr. Tihanyi emphasizes a cautious interpretation of the findings; the presence of weaponry does not automatically imply that SH-63 held the status of a warrior. The complexities of 10th-century social structures require careful analysis rather than assumptions drawn solely from archaeological artifacts.

Researchers assert that indicators such as joint changes or physical trauma often interpreted as evidence of martial activity might also stem from various daily life activities, including tasks related to horsemanship or other forms of labor. This aspect of analysis underscores the need for corroborative evidence before drawing definitive conclusions about the roles women played historically. Dr. Tihanyi’s insights further stir intrigue regarding the societal norms that governed life in 10th-century Hungary and the intersectionality of gender, occupation, and status.

This unusual burial holds the potential to catalyze extensive future research aimed at deeper investigations into other burials from the same period. By delineating patterns and variances of grave goods between male and female burials, researchers hope to establish a clearer picture of the dynamics that shaped gender roles during a time of significant upheaval. The findings of SH-63 pave the way for reimagining historical assumptions and igniting further discourse regarding the contributions and identities of women in early medieval societies.

The discovery of SH-63’s burial offers a novel perspective on 10th-century life in Hungary, suggesting that gender roles were likely more complex than previously acknowledged. The careful methods employed by Dr. Tihanyi and his team set a commendable precedent for future archaeological inquiries, encouraging a nuanced understanding of the past that recognizes the intricacies of societal roles across gender lines. As the ongoing investigations unfold, we stand on the brink of redefining our historical narratives and enhancing our comprehension of those who lived in a world marked by both strife and resilience.

Leave a Reply