Music possesses a profound ability to evoke memories and transport us to different eras or locations. A recent discovery from the realm of musicology highlights this phenomenon: a remarkable 55-note snippet of sheet music from 16th century Scotland has resurfaced, providing a glimpse into a musical tradition largely forgotten. Not only does this find bear historical significance, but it also serves as a cultural bridge to a time and place for which no extensive musical records have survived.

This fragment was unearthed from an intriguing source—the Aberdeen Breviary, published in 1510. While today it may not rank among the most popular or widely referenced texts, the Breviary is celebrated for being the first complete book printed in Scotland, holding a vital place in the historical timeline of Scottish literature. The collaboration among researchers from KU Leuven in Belgium and the University of Edinburgh enabled the analysis of this forgotten musical notation, shedding light on a previously obscure aspect of Scotland’s musical and religious fabric.

First Impressions and Analytical Insights

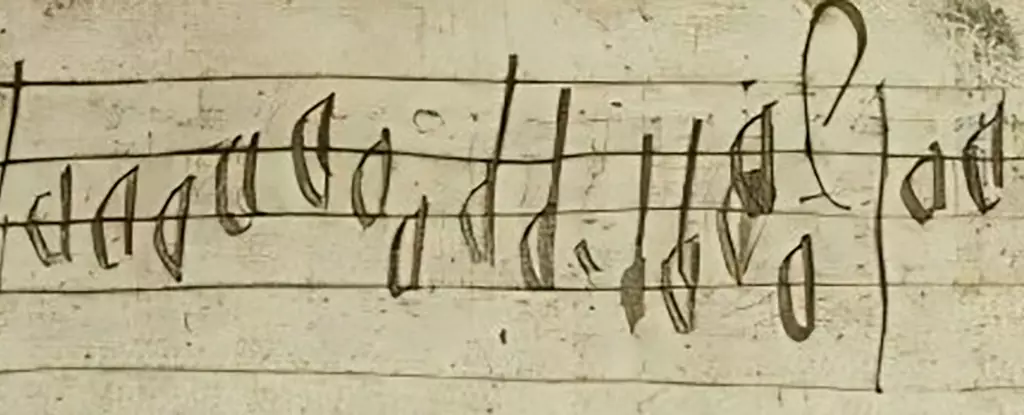

The sheet music was located in the margins of the Breviary, a testament to the notion that historical artifacts can possess layers of meaning beyond their initial appearance. This particular fragment, matching a less-known Christian chant known as *Cultor Dei, memento*—or “Servant of God, remember”—offers a tantalizing clue about the musical practices of pre-Reformation Scotland. While the researchers have not definitively determined whether the notes were designed to accompany a choir or instrumental performance, the discovery opens a window into Scotland’s liturgical music.

David Coney, a musicologist involved in the study, expressed the excitement surrounding this find, referring to it as a “small but precious artifact.” The reconstruction of the hymn from just a solitary line of music underscores the significance of this discovery. It captivates the imagination, allowing us to hear echoes of a melody that had faded into silence for nearly 500 years, providing richness to the Scottish musical landscape that scholars had previously assumed was barren.

What makes this fragment even more compelling is its designation as a polyphonic composition, indicating a sophisticated musical structure where two or more melodies coexist. This particular characteristic suggests that the music would have held a different aesthetic appeal, likely enriching the worship experience of those who participated in church services at the time. Its alignment with the tenor part of the known hymn opens possibilities for reconstructing additional harmonic parts that may have come into play.

As the research team meticulously disentangled the complex threads of musical notation, they identified the fragment as more than just a curiosity; it represents a tangible link to a vibrant musical tradition that thrived within Scotland’s ecclesiastical spaces. James Cook, another musicologist from the University of Edinburgh, points out the misinterpretation of pre-Reformation Scotland as lacking a robust musical culture, challenging long-held beliefs about this period’s artistic expression.

Furthermore, the study traced the ownership history of the Aberdeen Breviary, facilitating connections to significant religious sites such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St Mary’s Chapel in Rattray. However, the identity of the original composer remains a mystery, a common theme in the annals of music history where many voices have faded, leaving behind only whispers of their artistry.

This research also inspires scholars to deepen their examination of other historical texts, particularly those potentially containing hidden musical treasures nestled in margins and blank pages. Paul Newton-Jackson of KU Leuven emphasizes the potential for additional discoveries within 16th-century materials housed in Scotland’s libraries, suggesting that the legacy of Scotland’s musical heritage may be much more extensive than previously believed.

This 55-note fragment provides a vital link not only to Scotland’s past but also emphasizes the enduring nature of music as a cultural touchstone. The uncovering of such a significant artifact not only enriches our understanding of Scotland’s liturgical practices but also highlights the importance of continuous exploration within historical texts. For modern audiences and future generations, this rediscovered melody stands as a testament to the power of music in maintaining connections to our cultural heritage, reminding us that within the margins of history, stories—both musical and human—frequently lie in waiting to be discovered.

Leave a Reply