In a rapidly aging society, understanding the factors that influence cognitive health in older adults is paramount. Recent research aimed at unriddling the potential connection between antibiotic use and dementia risk has yielded intriguing results. A prospective study conducted over nearly five years has found no substantial link between antibiotics and increased dementia incidence in healthy older individuals. However, the implications of these findings are complicated and warrant a deeper dive into both the methodology and the broader context of cognitive health.

The research in question involved a comprehensive analysis of data from 13,500 older participants who took part in the ASPREE trial—an initiative designed to evaluate aspirin’s effects but evolved to monitor various health outcomes. Spearheaded by Andrew Chan, MD, MPH, from Harvard Medical School, the study indicated that antibiotic usage did not elevate dementia risk or cognitive impairment among its subjects (HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.84-1.25). This is particularly significant given that older adults frequently receive antibiotic prescriptions, leading to concerns about their long-term impacts on cognitive health.

Importantly, Chan’s study categorized antibiotic use through prescriptions filled, suggesting a focus on clinical practice rather than self-reported usage, which often contains biases. Yet, this method also introduces questions about the actual consumption of these medications and their real-world implications.

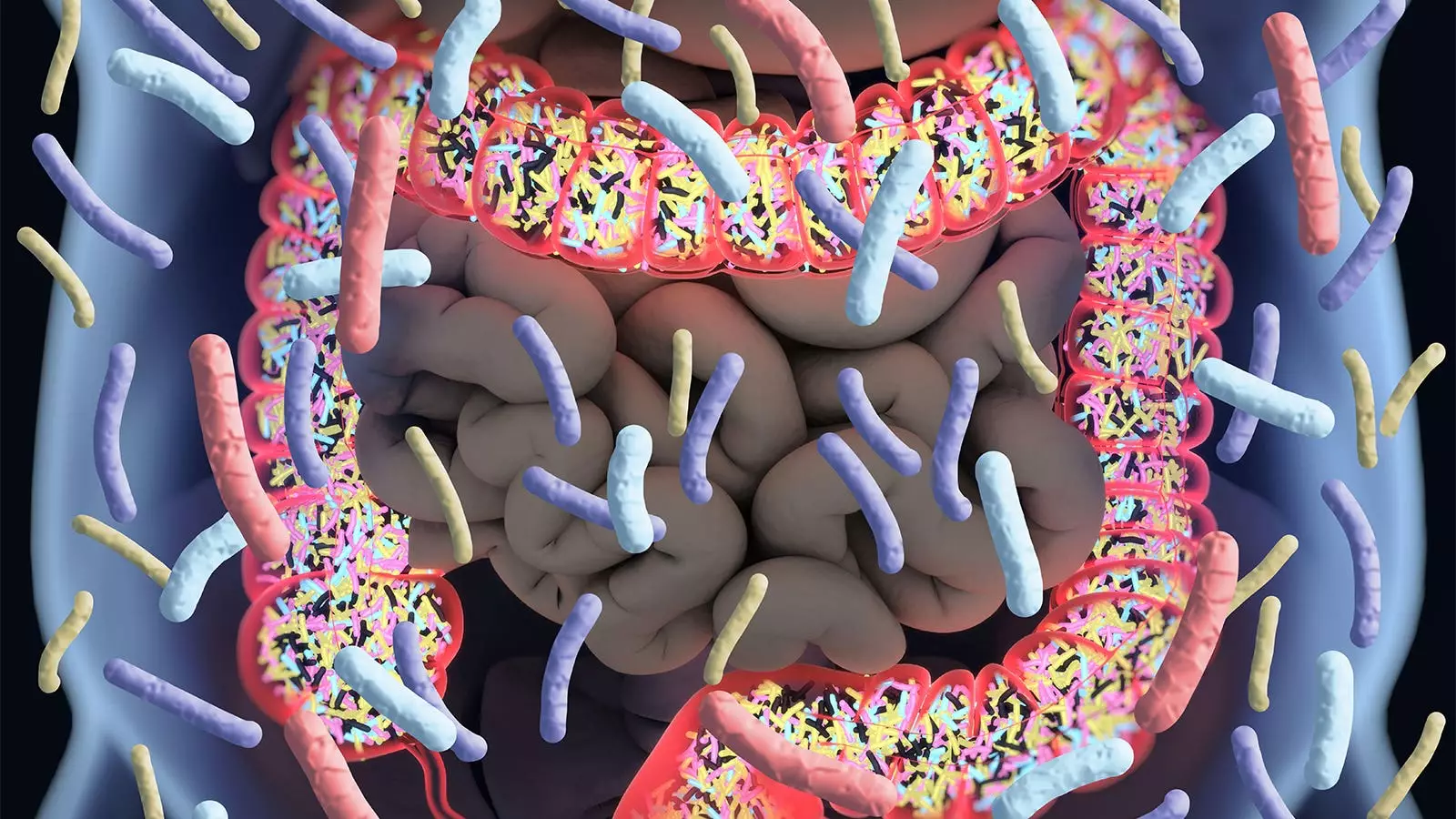

A focal point of concern in the discourse surrounding antibiotics involves their ability to disrupt the gut microbiome—a crucial element known to influence various health aspects, including cognitive function. Chan noted the apprehension surrounding potential adverse long-term effects on the brain from antibiotic use, as a balanced microbiome plays a role in maintaining both physical and mental health. Although the current study provides some reassuring insights for healthy older adults, the implications for those with pre-existing health issues remain unclear.

Furthermore, this juxtaposition between the gut’s microbiome health and cognitive decline opens a window into future research. If antibiotics disrupt these essential microbial communities, could there be indirect pathways leading to cognitive issues that merit further exploration?

The connection between antibiotic exposure and cognitive decline is not particularly straightforward. Previous research, including the Nurses’ Health Study II, suggested a different narrative, indicating that extended antibiotic exposure during midlife correlated with lower cognitive scores years later. Contradictory findings from diverse trials highlight the complexity of this relationship. For instance, earlier randomized trials hinted that short-term antibiotic treatment might mitigate cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients, while larger follow-ups suggested otherwise.

Such inconsistencies underscore the need for caution when interpreting findings and applying them to broader populations. The current study predominantly featured a specific demographic—healthy older adults with no serious underlying conditions. Hence, generalizing these results to the larger elderly population, which often grapples with a myriad of health challenges, might not do justice to the complexity of cognitive decline.

While the study cited no direct correlation between antibiotic use and dementia risk, its limitations must be carefully considered. The reliance on prescription records might not accurately represent participants’ actual medication consumption. Moreover, the sample’s health status at the study’s onset could skew results; a cohort that is generally healthier may respond differently to antibiotic treatments than individuals with existing health conditions.

Wenjie Cai, MD, and Alden Gross, PhD, from Johns Hopkins University, wisely emphasize the importance of a cautious approach to implementing these findings in clinical practice. The study’s insights are beneficial, but healthcare providers must remain vigilant regarding the broader implications for older adults who might experience different health trajectories.

Given the mixed findings surrounding antibiotic use and cognitive health, further investigation is paramount. Future studies should strive to include a diverse range of participants with varying health backgrounds. Exploring the nuances of how different classes of antibiotics impact cognitive functions could yield valuable insights. Additionally, longitudinal studies that can track not just antibiotic use but broader lifestyle factors impacting the gut microbiome and cognition will provide more comprehensive data.

This emerging research reframes the ongoing dialogue surrounding antibiotic prescriptions for older adults, revealing a landscape of both reassurances and caution. While no significant link between antibiotic use and increased dementia risk was found in healthy older adults, the dialogue about long-term health impacts remains far from settled. The need for more integrative research into cognitive health links is clear, paving the way for improved guidelines that resonate with the varied realities of the older population.

Leave a Reply