The growing epidemic of childhood obesity has compelled healthcare providers to explore innovative solutions to manage this complex condition. One emerging class of treatment options involves GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as liraglutide and semaglutide. As a pediatric obesity medicine specialist, I have witnessed notable successes with these medications in adolescents, yet the situation remains far more intricate for younger children. Understanding the evolving landscape of obesity treatment in children, particularly those under 12 years, presents a dichotomy of hope and caution for both clinicians and families alike.

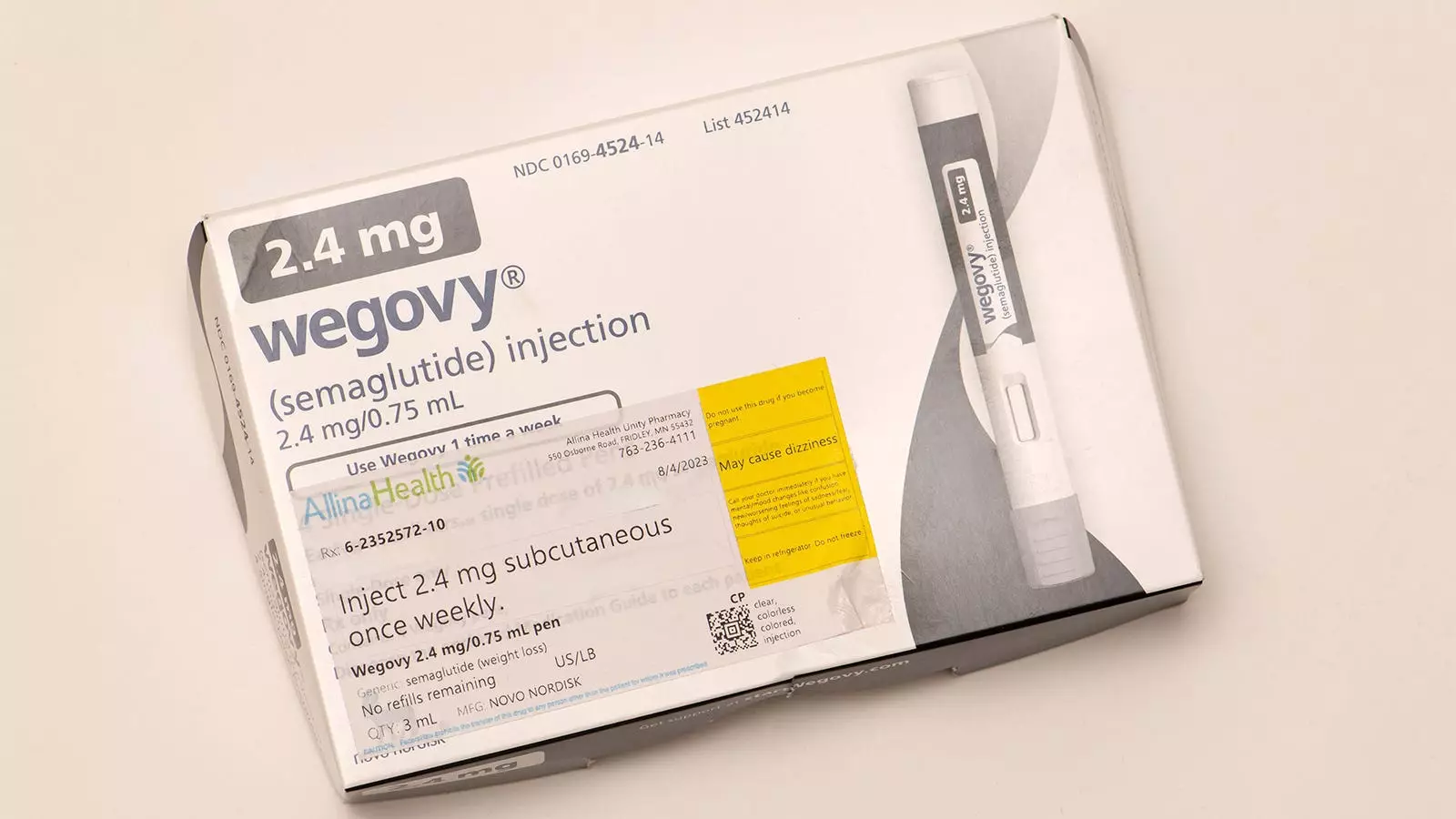

GLP-1 receptor agonists have recently ascended to prominence as impactful therapeutics in the fight against obesity. The considerable positive outcomes observed in adolescents receiving semaglutide, especially when supplemented with intensive behavioral lifestyle interventions, underscore the potential of these medications. Patients reported enhancements in physical health, well-being, and self-perception—all critical areas in tackling not just obesity but its associated comorbidities.

However, the story shifts dramatically when one turns attention to younger children. In this demographic, particularly those battling severe obesity or facing obesity-related complications such as prediabetes and psychological distress, existing medication options remain virtually non-existent. Currently, the FDA is weighing the approval of liraglutide for children aged 6-12—a move that could fundamentally alter treatment paradigms. But what does this mean for practitioners like myself, who are both hopeful yet deeply wary?

The prospect of liraglutide’s approval rests on the encouraging findings from a recent randomized controlled trial that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. This study involved 82 children and showed a significant reduction in BMI among those receiving liraglutide alongside behavioral interventions as opposed to those receiving only lifestyle coaching. The 5.8% decrease in BMI over 56 weeks shines a light on the possible effectiveness of such treatments, though the caveat remains—eighty percent of participants experienced gastrointestinal side effects.

For practitioners, this sets off alarms about the unknown long-term safety implications of this medication, particularly concerning growth and overall health in a developing child. While trends towards improvements in metabolic parameters were noted, the lack of statistically significant advancements raises questions regarding the real-world applicability and benefits of these pharmacotherapies.

Moreover, the knowledge that children may regain much of the weight lost following cessation of medication adds a further layer of complexity. Treatment termination resulted in a stark contrast between the treatment and placebo groups, leading to concerns about potential cycles of weight loss and gain, and how this might affect a child’s psychological health.

In the medical community, weighing the benefits against the risks is paramount, especially for young patients. The potential benefits of obesity pharmacotherapy in children can be summarized as follows:

– A modest reduction in BMI, which can significantly improve overall health.

– Improvements in metabolic markers, despite some lack of statistical significance.

– The possibility of enhancing psychosocial factors linked to obesity, despite studies currently lacking direct evidence in elementary-aged children.

Conversely, the risks associated with liraglutide treatment cannot be ignored. The uncertainties surrounding long-term safety raise significant red flags. Moreover, the fact that patients may experience weight regain once treatment concludes complicates the treatment narrative. There’s also the consideration of requiring daily injections, which can present significant barriers to adherence and acceptance, especially among young children and their families.

As we navigate this uncharted territory, individualization remains crucial. Treating severe obesity in children is not a one-size-fits-all approach; it necessitates in-depth discussions with caregivers about the risks and benefits of any pharmacological treatment versus the alternative of intensive lifestyle interventions.

The anticipated FDA approval of liraglutide may represent a pivotal moment, offering a new avenue for treating severe obesity in young children. Nonetheless, for me, the current landscape suggests that pharmacological treatments should remain a last resort, exercised judiciously and cautiously.

In closing, while the interest in pharmacotherapy for weight management in young children is commendable, it also calls for vigilant consideration. Researchers advancing our understanding of childhood obesity treatments are to be applauded, yet we must ensure that any new treatments are approached with the utmost caution and respect for this vulnerable population. There lies great potential for change, but responsibility in how we wield that power is paramount.

Leave a Reply